It seems hard to believe with drifts of snow heaped against the door, but today’s World Book Day coincides with the first meteorological day of spring. To celebrate, here is a review of Four Hedges by Clare Leighton, a book that rejoices in the earthiness of the garden.

Asphodel, Clare Leighton

Four Hedges is a pocket-sized delight. First published by Victor Gollancz in 1935 and reprinted by Little Toller in 2010, the book charts a year in Leighton’s Chiltern garden of the 1930s. Born in London in 1898, Clare Leighton was an artist, writer, designer and wood-engraver who emigrated to America in 1939, where she settled in North Carolina and taught at Duke University. As well as creating the woodcuts used in her own books, she also illustrated the works of Thomas Hardy, Gilbert White and Henry David Thoreau. Studded throughout with Leighton’s gem-like woodcuts of plants, flowers, birds and garden scenes, Four Hedges is part art exhibition, part memoir, and part discourse on the individual’s relationship with their home and the natural world around it.

Beginning in April with the ‘piercing grey winds’ of early spring, Four Hedges walks us through Leighton’s garden month by month. It begins by drawing parallels between the worlds of horticulture and theatre: ‘[t]he drama of the year is late in starting and I am in time for the first act.’ This is no how-to-garden guide, but a psychogeographic exploration by an artist of a place intimately known. Arriving back in the Chilterns from a holiday in Corsica, Leighton notes that her return brings with it a sense that her ‘year is out of focus’, the heat of the Mediterranean putting her disjointedly out of step with her garden.

Leighton reconnects to her garden – and to her reality – through digging its earth with her bare hands. Even when she spikes her foot on a thistle, ‘there is this feeling of goodness coming up into me from the ground’. In the 1930s she was already warning her readers against growing too detached from the physical world:

‘We are losing much, these days, when we no longer get this naked contact with the earth. The sensation of touch seems to be fading, and lazily we look at things with our eyes, and smell the more pronounced scents around us, ignoring the vast range of emotion that is within the scope of hand or foot […] we are poor creatures that we should call ourselves civilised, we who have only these blunted powers’.

Four Hedges, p.92

Although Leighton’s book is no gardening guide, it nevertheless imparts snippets of countryside lore from generations past. Lacey, Leighton’s gardener with a ‘rumbling, earthy voice’, is a Chiltern native who embodies the folk wisdom of an older England. The adage that fair weather at Candlemas is the sign hard winter weather still to come introduces Leighton’s February chapter, and I see that 2018, like 1935, has a February that disappears into a blizzard:

‘By midday the snow has started, blown horizontal across the land by the violent winds, it lies in a thin scatter on the hill-tops, transforming them into high mountains. By nightfall it has begun to settle, and […] I listen in bed to that absolute silence without, which comes upon the earth only when it is covered with snow.’

Four Hedges, p.147/8

As I write this the weather is bitterly cold, snow whirling around the house like an icy dervish. Our village’s main road passes by our house, but for the last two says snow has muffled ‘the ugly sounds of civilisation’, plunging us into a near-silent world. Reading Leighton’s winter chapters makes me feel doubly connected to this weather as it rattles hail down the stove pipe and flings gobbets of snow at our windows.

Bullfinch swinging on the weigela

Standing in the kitchen window I see three goldfinches jostling for space on the bird feeder, and by the hedge a blue tit pokes its beak into the brittle orange beech leaves that still linger from the autumn. As Leighton observed, the white blankness of the snow makes the colours of the birds jump out as its white blankness ‘heightens and burnishes the greys and browns of sparrow and thrush […] dull colours that would pass unnoticed against the usual background of earth and field become infused with life when they stand against snow’.  Two bullfinches bounce bright into my garden, puffed up against the weather. The male, vivid coral pink at his breast, swings from the slender branches of the bare weigela, pecking off its buds in his hunger. Under the nearby cypress his pale buff mate nestles her feather-bulk into the mulch of leaves, twigs and grass on the ground, flicking over leaves with her beak in the hunt for insects. The gold finches flash their war-painted red and black faces at each other as they attack the nyger seed, their black and yellow wings a fluttering blur as they compete to perch on the feeder.

Two bullfinches bounce bright into my garden, puffed up against the weather. The male, vivid coral pink at his breast, swings from the slender branches of the bare weigela, pecking off its buds in his hunger. Under the nearby cypress his pale buff mate nestles her feather-bulk into the mulch of leaves, twigs and grass on the ground, flicking over leaves with her beak in the hunt for insects. The gold finches flash their war-painted red and black faces at each other as they attack the nyger seed, their black and yellow wings a fluttering blur as they compete to perch on the feeder.

As Leighton and I share our gardens and the weather, I feel closer to both through comparing our worlds, seeing my world the sharper for its reflection in hers. Like her woodcuts, Leighton’s prose is precise and clear, clarifying the smudged, untidy world. With her I luxuriate in the ‘gentle, growing rain’ of April with its ‘silky rustle’; thrill at the prospect of ‘sunshine and swallows, apple blossom and cowslips’ when ‘the skirts of the hedges froth white with cow parsley’ in May; and imagine holding my new baby come June when ‘the garden is a nursery of nests and young birds’. My favourite season, autumn, arrives with apples knocked to the ground in a thunderstorm, this new year-spell ‘gently showing the marks of its fingers in heavy morning dews’.

Leighton’s is truly an artist’s experience of the world, alive to movement and colour, smell and touch. It seems only fair to let her have the last word, on this day of spring and books:

‘Spring is upon us, and will not be hindered by winds or rain, or scurries of snow.’

Happy World Book Day from snowy Ceres

I love reading books when I’m sat in the place they are set in, mixing the pleasure of being transported to a different time whilst staying in the same geographic location. I feel like I’m slipping between the universe’s folds, watching a story play out in front of me somewhere between the time it happened in and now. Last month my husband and I were on holiday in the Welsh borders, and whilst he headed out to bag some hills I took myself off to Brecon to amuse myself in bookshops and cafes. It was strange day, the day after the UK’s referendum on its membership of the EU, and I found myself listening to the lilting Welsh accents around me to hear local reactions to the vote. After an hour or two pouring over the papers in the library and feeling cross, I hopped across the road to

I love reading books when I’m sat in the place they are set in, mixing the pleasure of being transported to a different time whilst staying in the same geographic location. I feel like I’m slipping between the universe’s folds, watching a story play out in front of me somewhere between the time it happened in and now. Last month my husband and I were on holiday in the Welsh borders, and whilst he headed out to bag some hills I took myself off to Brecon to amuse myself in bookshops and cafes. It was strange day, the day after the UK’s referendum on its membership of the EU, and I found myself listening to the lilting Welsh accents around me to hear local reactions to the vote. After an hour or two pouring over the papers in the library and feeling cross, I hopped across the road to

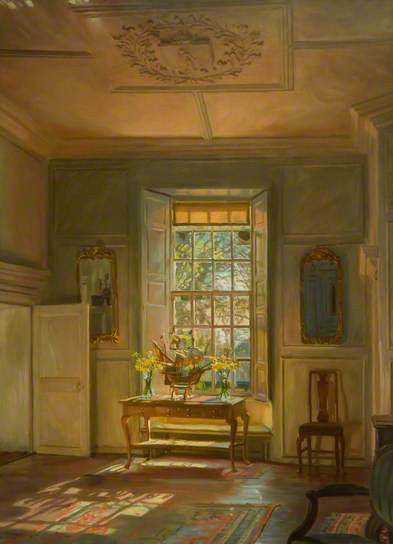

I’m making a small step in this direction later this month, moving from the bustle of Edinburgh to the rolling hills of Fife. We’ll be taking on the lease of a small cottage in the village of Ceres, and I can’t wait to have a garden to tend again and a kitchen bigger than a cupboard to cook in. The house (the middle one in the picture above) is older than most of the places we’ve lived in and we’ll have to walk over an ancient footbridge to get home each day. There’s no farm to tend, but I can’t wait to have space to roam in the evenings, and leave the omnipresent drone of cars and the wailing sirens behind. Edinburgh, you’ve been grand – but my heart’s in the country.

I’m making a small step in this direction later this month, moving from the bustle of Edinburgh to the rolling hills of Fife. We’ll be taking on the lease of a small cottage in the village of Ceres, and I can’t wait to have a garden to tend again and a kitchen bigger than a cupboard to cook in. The house (the middle one in the picture above) is older than most of the places we’ve lived in and we’ll have to walk over an ancient footbridge to get home each day. There’s no farm to tend, but I can’t wait to have space to roam in the evenings, and leave the omnipresent drone of cars and the wailing sirens behind. Edinburgh, you’ve been grand – but my heart’s in the country.

Thank God for Chitra Ramaswamy. Her brand new book Expecting: The Inner Life of Pregnancy (Saraband, April 2016) is a magical yet practical and beautifully written monologue on pregnancy, from the pre-conception jitters to the miraculous but traumatic moment of birth. Each chapter follows a month of her own pregnancy but against a background of cultural and literary references from Sylvia Plath to Tolstoy. In fact, those two sources are pretty important, because there simply aren’t that many books, poems, plays, films or works of art which actually depict this most awesome and fundamental of human processes. As Ramaswamy questions:

Thank God for Chitra Ramaswamy. Her brand new book Expecting: The Inner Life of Pregnancy (Saraband, April 2016) is a magical yet practical and beautifully written monologue on pregnancy, from the pre-conception jitters to the miraculous but traumatic moment of birth. Each chapter follows a month of her own pregnancy but against a background of cultural and literary references from Sylvia Plath to Tolstoy. In fact, those two sources are pretty important, because there simply aren’t that many books, poems, plays, films or works of art which actually depict this most awesome and fundamental of human processes. As Ramaswamy questions:

This is a fairly roundabout way of approaching Katherine Swift’s The Morville Hours, but the reason for doing so is because Swift is so astonishingly good at entwining the languages of gardener, builder, priest, beekeeper and a multitude of others into her narrative. The Morville Hours tells the story of Swift’s life and garden using the dual frameworks of the mediaeval book of hours on one hand and England’s traditional horticultural calendar on the other. Both are potentially off-putting subjects in their extreme specificity and almost complete irrelevance to our city-centred modern lives, but in Swift’s exquisite prose both become fascinating and beautiful in their complexity. I found that although I didn’t know what many of the words Swift used meant precisely – the list includes terce, none (pronounced to rhyme with ‘one’ and ‘stone’, not ‘bun’ and ‘fun’), achillea ptarmica, and a hundred other plant names. But it didn’t stop me understanding Swift’s story, and I didn’t mind not knowing as she made me feel that a world was opening up to me through these words, not shutting me out. The Morville Hours is a magical book in that it has the power to transport, translate and transmorgrify things of which I was completely ignorant into fascinating subjects that I just want to more and more about.

This is a fairly roundabout way of approaching Katherine Swift’s The Morville Hours, but the reason for doing so is because Swift is so astonishingly good at entwining the languages of gardener, builder, priest, beekeeper and a multitude of others into her narrative. The Morville Hours tells the story of Swift’s life and garden using the dual frameworks of the mediaeval book of hours on one hand and England’s traditional horticultural calendar on the other. Both are potentially off-putting subjects in their extreme specificity and almost complete irrelevance to our city-centred modern lives, but in Swift’s exquisite prose both become fascinating and beautiful in their complexity. I found that although I didn’t know what many of the words Swift used meant precisely – the list includes terce, none (pronounced to rhyme with ‘one’ and ‘stone’, not ‘bun’ and ‘fun’), achillea ptarmica, and a hundred other plant names. But it didn’t stop me understanding Swift’s story, and I didn’t mind not knowing as she made me feel that a world was opening up to me through these words, not shutting me out. The Morville Hours is a magical book in that it has the power to transport, translate and transmorgrify things of which I was completely ignorant into fascinating subjects that I just want to more and more about.

3) Names the for Sea, Sarah Moss (2013)

3) Names the for Sea, Sarah Moss (2013) Nature writing combined with a tale of recovery from breakdown – two of my very favourite genres combined into a truly beautiful memoir of life in and between Orkney and London. Liptrot has been lauded as a new voice in the nature writing tradition, and I think her work has striking similarities to both Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain and Gwyneth Lewis’ Sunbathing in the Rain. It’s only just come out (January 2016) so if you can lay your hands on a copy then do, you really won’t be disappointed. You can read my review of it here:

Nature writing combined with a tale of recovery from breakdown – two of my very favourite genres combined into a truly beautiful memoir of life in and between Orkney and London. Liptrot has been lauded as a new voice in the nature writing tradition, and I think her work has striking similarities to both Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain and Gwyneth Lewis’ Sunbathing in the Rain. It’s only just come out (January 2016) so if you can lay your hands on a copy then do, you really won’t be disappointed. You can read my review of it here:

The main culprit for this for me is

The main culprit for this for me is

As the title suggests, the book charts one calendar year in Russell’s life in Denmark. Each chapter ends with a summary of the things about ‘living Danishly’ that Russell has learned during that month. January is for ‘hygge and home’, hygge being that fashionably Danish concept of wood-fired candle-lit cosiness, during which we learn that Denmark is cold in January, owls are loud, and immigration is not for the faint-hearted. By June Russell’s in the middle of a hormonal three-to-six month nosedive on the culture shock curve, and it’s time for a cold hard look at Danish feminism. But twelve months after arriving, Russell and her husband decide to stay for another year and the book ends with a list of twelve excellent ways to ‘live Danishly’, wherever you lay your hat. Trust more, get hygge, use your body, make your home nice, streamline your options, be proud, value family, be equally respectful, play, and share. These are the things that Russell identifies as being at the root of Danish happiness, and I have to say they make pretty attractive reading: I wanted to move to Norway more than ever after reading her book.

As the title suggests, the book charts one calendar year in Russell’s life in Denmark. Each chapter ends with a summary of the things about ‘living Danishly’ that Russell has learned during that month. January is for ‘hygge and home’, hygge being that fashionably Danish concept of wood-fired candle-lit cosiness, during which we learn that Denmark is cold in January, owls are loud, and immigration is not for the faint-hearted. By June Russell’s in the middle of a hormonal three-to-six month nosedive on the culture shock curve, and it’s time for a cold hard look at Danish feminism. But twelve months after arriving, Russell and her husband decide to stay for another year and the book ends with a list of twelve excellent ways to ‘live Danishly’, wherever you lay your hat. Trust more, get hygge, use your body, make your home nice, streamline your options, be proud, value family, be equally respectful, play, and share. These are the things that Russell identifies as being at the root of Danish happiness, and I have to say they make pretty attractive reading: I wanted to move to Norway more than ever after reading her book.

The narratives of chased and chasing are familiar to me from another autobiography of alcoholism and depression, Gwyneth Lewis’ Sunbathing in the Rain. Both describe the out-of-control searching for something at the bottom of a bottle, the desperate efforts to escape from or to a place by being the drunken sailor on a tipsy ocean. But where as Lewis’ drinking is an attempt to outrun her own depression (and her mother’s), Liptrot’s seems to be an attempt to catch up with the violent mood swings of her father, to mimic the highest highs and terrible lows that shaped her childhood. She’s almost drinking to outrun him, not herself, to go higher and faster and giddier with each bottle.

The narratives of chased and chasing are familiar to me from another autobiography of alcoholism and depression, Gwyneth Lewis’ Sunbathing in the Rain. Both describe the out-of-control searching for something at the bottom of a bottle, the desperate efforts to escape from or to a place by being the drunken sailor on a tipsy ocean. But where as Lewis’ drinking is an attempt to outrun her own depression (and her mother’s), Liptrot’s seems to be an attempt to catch up with the violent mood swings of her father, to mimic the highest highs and terrible lows that shaped her childhood. She’s almost drinking to outrun him, not herself, to go higher and faster and giddier with each bottle.