In the Blood – A Memoir of My Childhood, Andrew Motion (Faber, 2006)

On a dreary January day I picked up this book, knowing virtually nothing about Andrew Motion except that he’d been the ‘safe choice’ Poet Laureate before Carol Ann Duffy, and that he’d once refused permission to use a recording of one of his poems in a small exhibition on classic poetry. I did not have the impression of him as someone who would write a particularly fascinating autobiography.

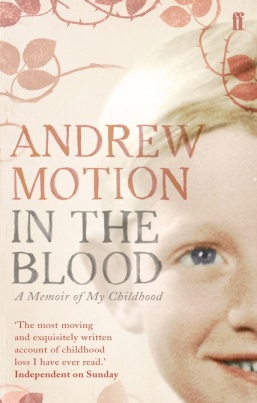

However, I was curiously drawn to it, not least because I had a long afternoon stretching out before me when my only task was to print and fold hundreds of letters, so anything was a welcome distraction. And as so often is the case with Faber, the book itself is an attractive book, with red thorns curling across the cover and the title and author’s name picked out in red and black tipsy capitals. Printed on textured paper, it felt slightly rough to the touch, but the spine seemed unbroken, the pages unthumbed. A bad omen?

However, I was curiously drawn to it, not least because I had a long afternoon stretching out before me when my only task was to print and fold hundreds of letters, so anything was a welcome distraction. And as so often is the case with Faber, the book itself is an attractive book, with red thorns curling across the cover and the title and author’s name picked out in red and black tipsy capitals. Printed on textured paper, it felt slightly rough to the touch, but the spine seemed unbroken, the pages unthumbed. A bad omen?

As it turns out, no. In the Blood is a bloody book: Motion’s family are upper middle-class and hunt, shoot and fish with their set, and Motion appears both smeared in fox blood and dripping with the blood of a recently-shot deer at various points. Although I am not an advocate of blood sports, this detail served as a particularly visceral metaphor for the vicissitudes of growing up, whilst placing Motion firmly in a recognisable social milieu .

Motion (and how fitting to have such a vibrant abstract noun as your surname) is a deft turner of phrase and tale. His autobiography opens with the description of one day in late adolescence. The themes of first love, or at least first lust, and burgeoning adulthood quickly shift towards the side of the lens through which we are looking at Motion’s life, as a far greater and darker event is about to overshadow his world. We then jump back to early childhood, and then further back into the half-remembered, half-mythologised world of older Motions and Bakewells.

However, when he gets to senior school (Radley College) time seems to slip from Motion’s grasp. He’s preparing for his O-levels, and then suddenly he’s 12 years old again, and mere paragraphs later he’s about to start his A-levels. Before long I’d lost track of the order of what happened during his teenage years; perhaps this was simply mimetic of the confusion that he felt during that time (although it seems to be the period in which Motion felt most comfortable and purposeful), but it struck me as slightly lazy writing, as if he almost couldn’t be bothered to write as carefully as he had done in earlier chapters.

However , as you might expect from a poet, the crafting of the words themselves is the book’s redeeming feature. Never mind poetry in motion, this Motion’s prose is as lively, vivid and dramatic as you could wish for in autobiographical writing. He inhabits the mind of his younger self with convincing ease, presenting conversations and memories in such a moving and authentic way that you have to remind yourself that these infant rememberings must be coloured with the filter of adult comprehension. Motion and his readers seem tragically drawn towards his mother, and the book is peppered with premonitions of her final illness and fragility. These hints always spurred me on to find out what would happen to her – and Motion himself. I began to care for them as a family, their struggles and actions seeming wholly real, sometimes sad and often endearing. It mixed pathos with humour and resilience, and made real and rounded characters of Motion’s family. And it made me want to read his poetry, in part to see if any of these episodes had crossed over from prosody into verse.

What’s next? I am impatiently waiting for a delivery of Tove Jansson’s new biography Life, Art, Words so expect to see a review of it on here very soon!